Market focus has shifted from elections to central banks’ next steps

Financial markets, having digested the result of parliamentary and/or presidential elections in the US, Austria, Netherlands, France and UK and expecting German Chancellor Angela Merkel to win a fourth consecutive general election on 24th September, have turned their focus to global central bank policy. Specifically, it has centred on the possibility of tighter interest rate policy in developed economies in the form of rate hikes and/or modifications to central bank balance sheets or quantitative easing programs.

End-2016 proved to be an important inflexion point for global central bank policy

Up until the summer of 2016, developed central banks were still very much in monetary easing mode, with the exception of course of the Fed which had hiked its policy rate 25bp in December 2015. But eight years of ultra-low (and in some cases negative) central bank policy rates and expansive bond-buying programs had helped stabilise global growth and inflation, albeit at low levels. At the same time, the costs of ultra-loose monetary policy, including asset price bubbles, distortions in bond markets, pressure on the banking sector and even rising inequality, had started to outweigh the benefits.

This led to me to forecast that major central banks may refrain from loosening monetary policy further and that the ECB and BoE would keep the modalities of their QE programs broadly unchanged near term. At the very least I expected central bank policy rate cuts to become increasingly less frequent than in the past and that the world’s most influential central bankers would start tweaking a discourse which had in recent years largely focused on doing “whatever it takes” (see Global central bank easing nearing important inflexion point, 16 September 2016).

At the same time I argued that bar the Fed and possibly a handful of emerging market central banks still fighting weak currencies and high inflation, no major central bank was likely to hike policy rates or tighten monetary policy in the remainder of 2016 – that was a story for 2017, at the earliest.

This scenario has largely materialised, with the exception of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand delivering a final 25bp rate hike in November 2016.

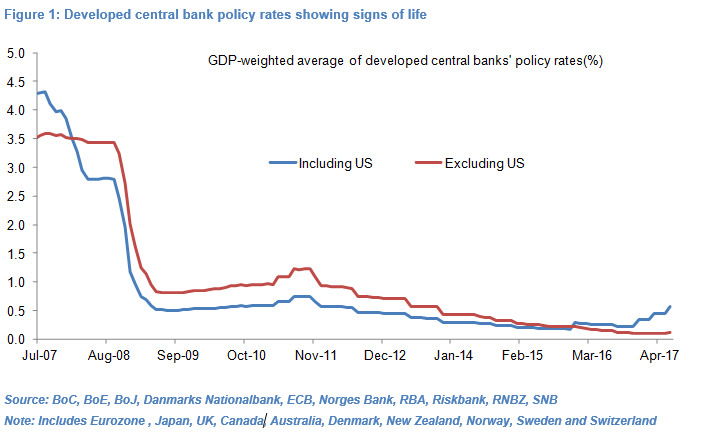

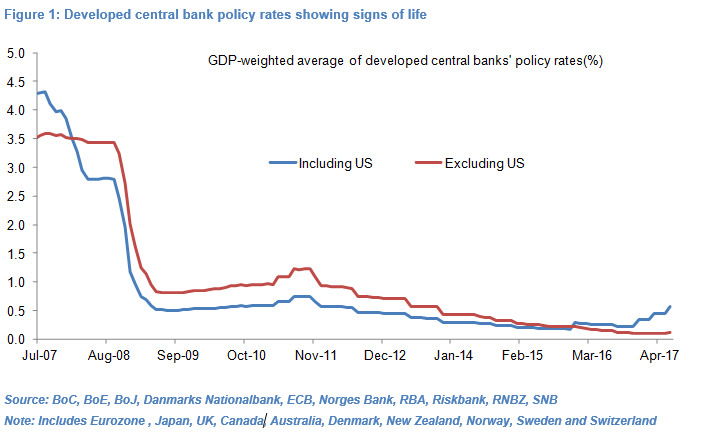

- Since then no developed central bank has cut its policy rate with a GDP-weighted average of policy rates bottoming out and more recently inching higher (see Figure 1).

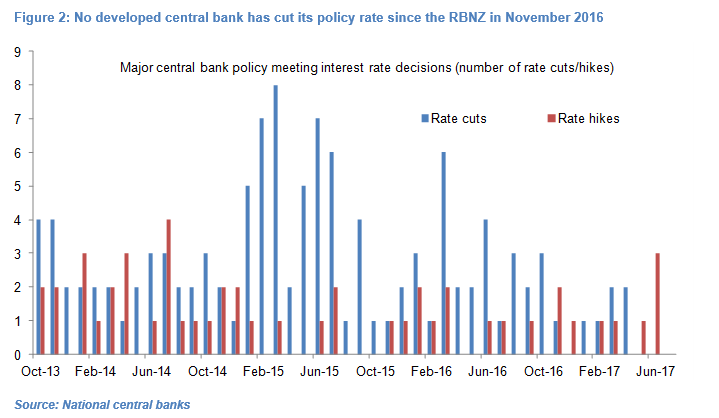

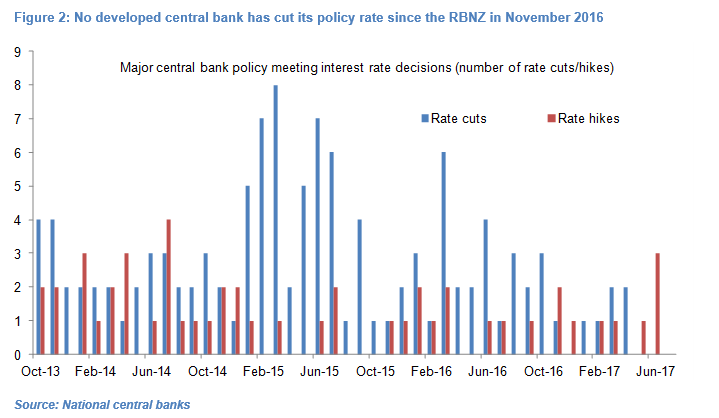

- The only major central banks to have cut rates are the Central Bank of Russia and Banco Central do Brazil (see Figure 2). In May and June 2017 no major central bank cut its policy rate – the only other time this has happened in the past four years was in December 2016.

- Central banks in Turkey and Mexico, in the face of still high inflation, have hiked their policy rates 50bp and 225bp respectively since August 2016.

- The US Federal Reserve has already hiked rates 50bp this year and there has been growing talk of the Fed shrinking the size of its balance sheet.

- This week the Bank of Canada hiked its policy rate (25bp) for the first time in nearly seven years.

- Three out of eight members of the Monetary Policy Council of the Bank of England dissented in favour of a 25bp rate hike at the June policy meeting.

- The European Central Bank has adopted a marginally more hawkish language in recent months. There is mounting expectation that the ECB will announce as early as September an extension of its quantitative easing program beyond-2017 but also a gradual tapering of the monthly amount of bonds purchased (from €60bn currently), with QE ending fully in late 2018 or early 2019.

This has led to growing speculation that we have reached a second inflexion point in developed central bank policy and one which could be sharp enough to dislocate global growth and asset markets, particularly in emerging economies. But financial markets, at present, expect only very marginal policy tightening by developed central banks. Specifically:

- US Federal Reserve: Markets have all but priced out a September hike and are pricing in only another 12bp of hikes by year-end (i.e. a 50% probability of one more 25bp hike this year)

- Bank of England: 12bp of hikes priced by year-end (i.e. a 50% probability of one hike this year)

- Reserve Bank of Australia: No hikes priced in for the remainder of the year and only 15bp of hikes priced in for the next 12 months.

- Bank of Canada: One more 25bp hike priced for this year.

This skinny market pricing of policy rate hikes is appropriate, in my view. At a global level, there are signs that GDP growth may have plateaued in Q2 2017 at around 3.1-3.2% year-on-year (see Figure 3), as I argued in H2 2017: Something old, something new, something revisited (23 June 2017).

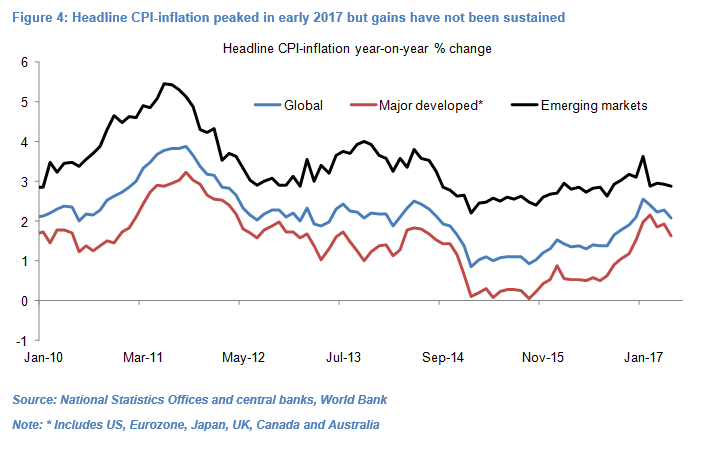

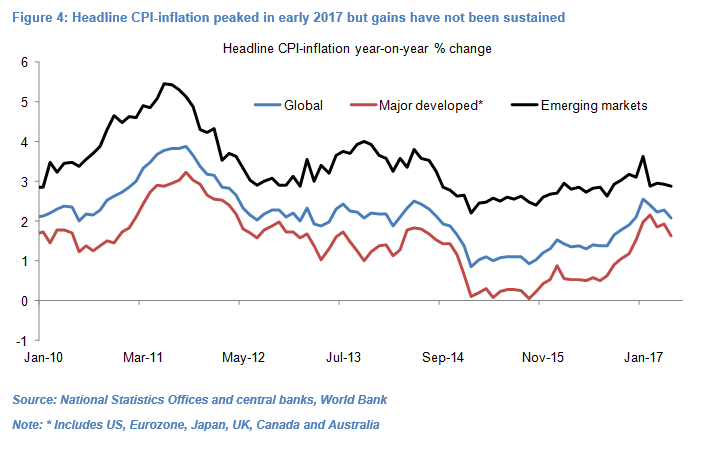

Moreover, inflationary pressures remain muted in developed economies. Headline CPI-inflation in both developed and emerging market economies steadily rose between end-2015 and early 2017 but has since fallen (see Figure 4).

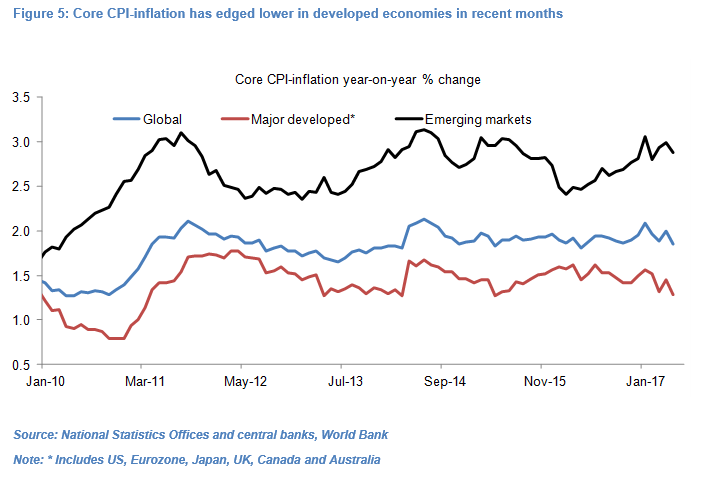

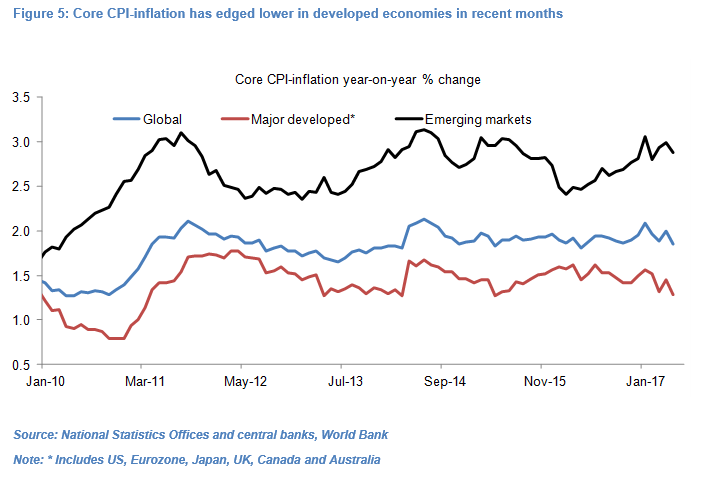

Perhaps more importantly, core CPI-inflation, which strips out food and fuel prices, has risen in emerging markets but after having flat-lined for years in major developed economies has in recent months dipped lower (see Figure 5). Only in the UK has core CPI-inflation risen and this is mainly attributable to higher imported inflation fuelled by the collapse in Sterling following the 23rd June 2016 EU referendum.

Moreover, in the US and Australia positive employment growth and very low unemployment rates continue to go hand in hand with only modest growth in real wages, while in the UK real wages are falling – an issue which I first identified in The common theme of low-wage growth, 10 February 2017). The inability of workers to command larger increases in nominal wages is acting as a break on both inflation expectations and consumer demand, and in turn is likely to curb underlying inflation going forward, in my view.

Bank of England – Policy rate to remain on hold in August and potentially rest of the year

The weakness of the UK economy and uncertainty associated with the Brexit process are high enough hurdles for the Bank of England (BoE) to refrain from hiking policy rates any time soon (see UK: Land of hope & glory…but mostly confusion, 7 July 2017).

I maintain my view that the BoE’s eight-member MPC is unlikely to hike its policy rate of 0.25% at its August meeting. While I expect MPC member Andrew Haldane to join Michael Saunders and Ian McCafferty in voting in favour of a 25bp hike, new member Silvana Tenreyro is likely to vote in favour of no change which would result in a 3 versus 5 vote in favour of rates remaining on hold. Importantly, I believe that Governor Carney – who has the casting vote in the event of a 4 versus 4 tie – will again vote for no change, even if he has had a tendency to blow hot and cold.

US Federal Reserve – Skip September meeting, keep December alive?

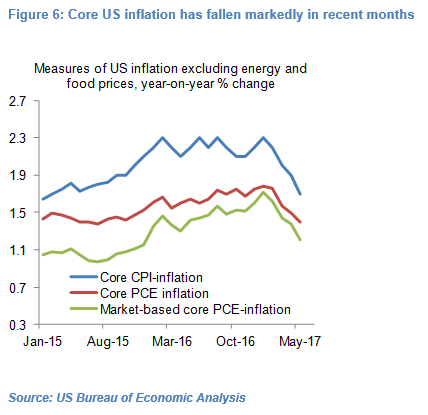

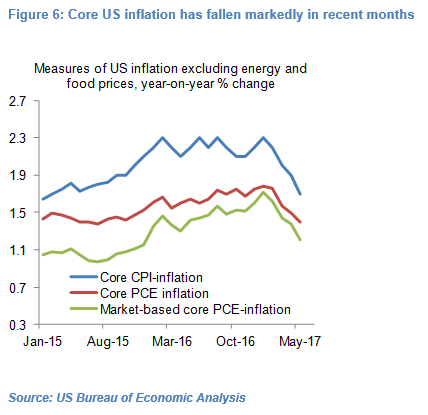

The US Federal Reserve has hiked its policy rate 50bp year-to-date but markets, which are pricing only 12bp of hikes for the remainder of the year, are clearly divided as to whether FOMC members will stick to their end-2016 forecast that three hikes would be appropriate in 2017. My core scenario remains that the Fed will not hike rates again in 2017 although this is a modest conviction call. While the labour market is inching towards full-employment, measures of US core inflation have fallen as pointed out by a number of FOMC members, including Chairperson Janet Yellen (see Figure 6).

The Reserve Bank of Australia has given every indication that it will remain pat on interest rate policy for the foreseeable future and while the Bank of Japan is prone to tweaking inflation targets and yield targets I do not foresee major policy changes at this juncture.

Olivier Desbarres

Olivier Desbarres currently works as an independent commentator on G10 and Emerging Markets. He has over 15 years’ experience with two of the world’s largest investment banks as an emerging markets economist, rates and currency strategist.