The month of August has come and gone and I struggle to pinpoint any new, clear-cut common themes. There has been plenty of news and developments for financial markets to digest and react to, including North Korea’s recent missile launch over Japanese airspace, the devastating impact of hurricane Harvey in Texas, the looming US debt ceiling breach, President Trump’s threats of terminating/re-negotiating NAFTA, ongoing Brexit negotiations between the UK and European Union and French President Macron’s announcement of ambitious labour market reforms.

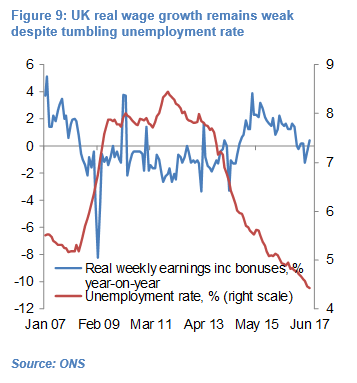

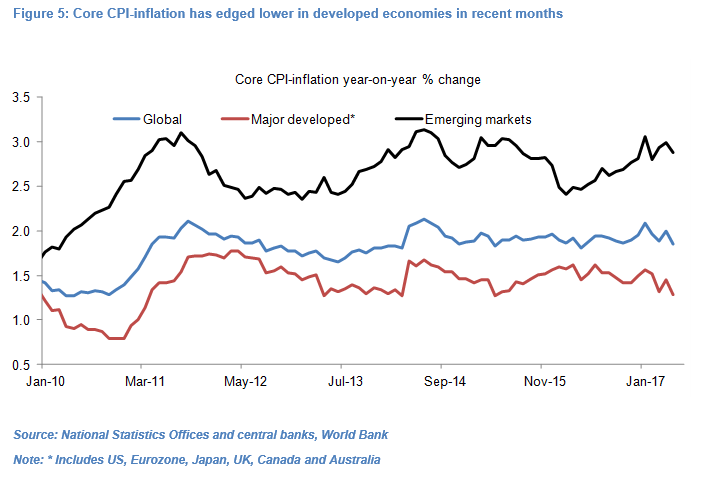

However, the Economic Policy Symposium in Jackson Hole on 24-26 August promised a lot but as often the case delivered little for markets to hook their teeth into. Moreover, macro data in the past few weeks have not really told us anything really new. Gains in global GDP growth are incremental but 3% seems like a reasonably robust floor. Today’s global manufacturing PMI data for August (due for release at 16:00 London time) are worth paying attention to given the decent correlation with global GDP growth according to my analysis (see Figure 1).

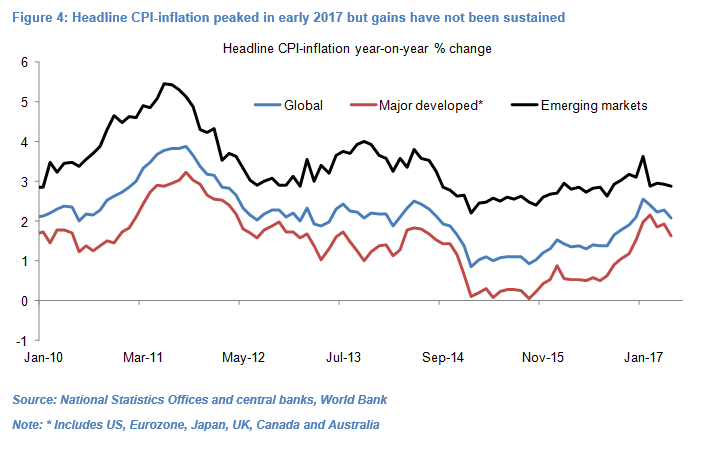

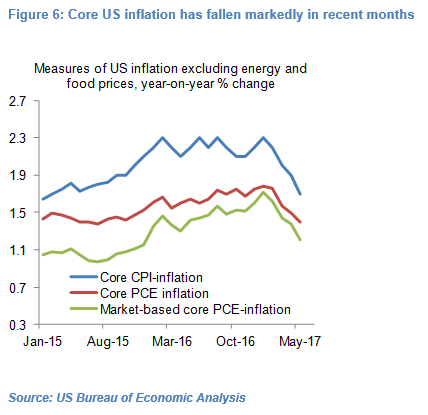

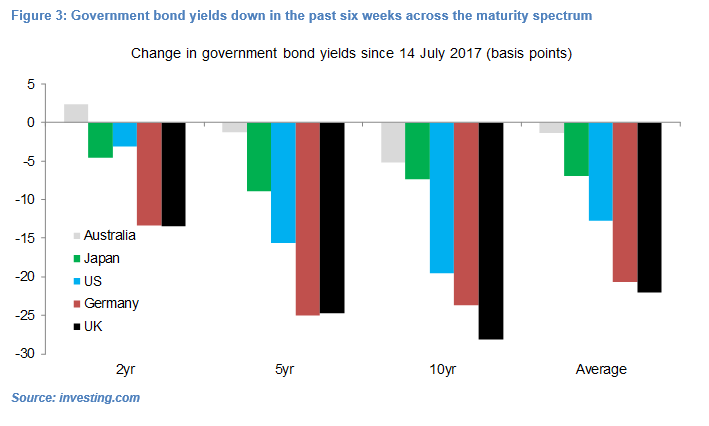

The mirage of much higher inflation in developed economies remains largely just that – a mirage – which I attribute in part to tepid real wage growth – at least in the US, Australia and in particular the UK. This presents somewhat of a dilemma for the Federal Reserve, far less so for the Bank of England and Reserve Bank of Australia as I discuss below.

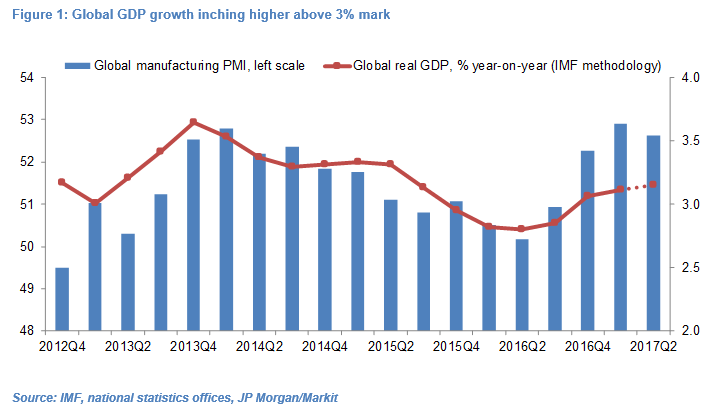

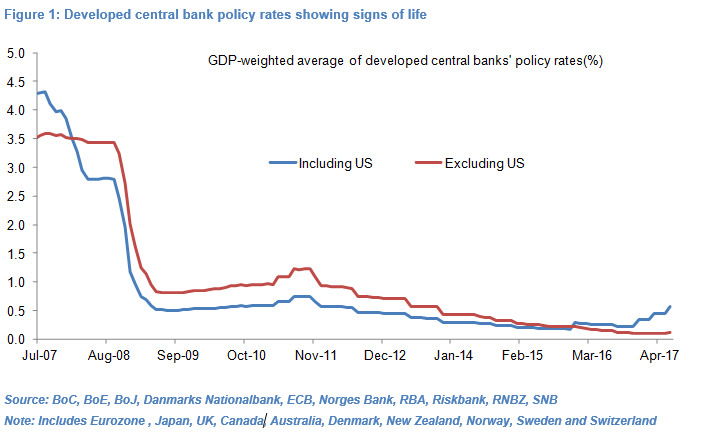

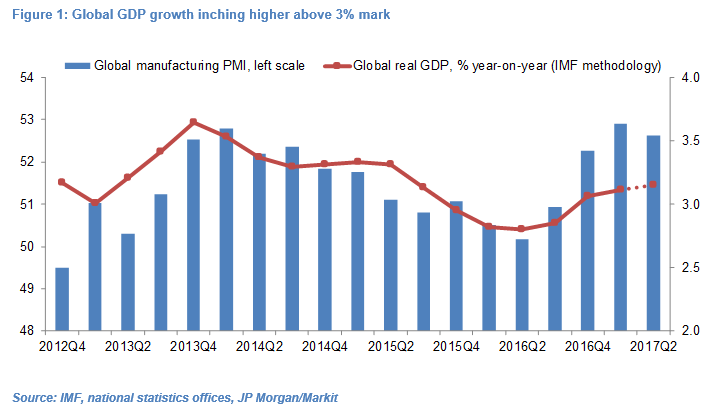

This explains in large part the dovish bias in global rate markets, with government bond yields in the US, UK, Germany and Japan continuing to slowly edge lower (see Figure 2). This trend in developed market yields is broadly in line with the view I expressed six weeks ago that skinny market pricing of policy rate hikes was probably appropriate (see Central banks – a muted second inflexion point, 14 July 2017).

The fall in yields has been pervasive across the maturity spectrum and only Australian 2-year bond yields have risen (albeit by a paltry 2bps since mid-July – see Figure 3).

Markets showing Teflon-like qualities but September may offer more acute test

There is also an argument to make that markets’ threshold for change is seemingly quiet high. The VIX equity volatility index temporarily spiked to 14 a few days ago but is now back on a 10-handle and the Dow Jones is grinding back higher. Sterling has been reasonably well behaved in the past week while the Euro, the poster-boy of developed currencies for the past five months, is struggling to extend its gains (in nominal effective exchange rate terms).

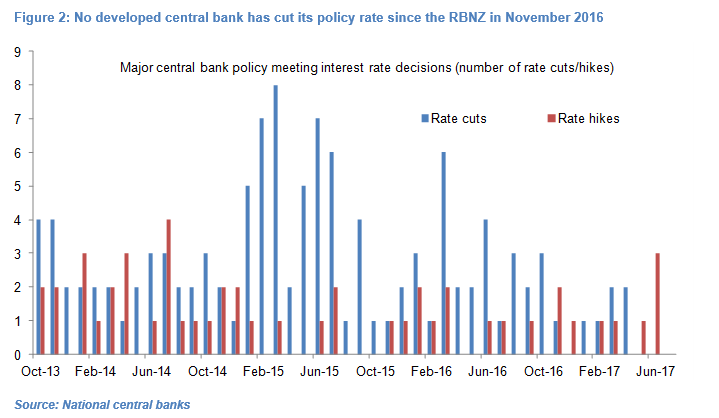

Event risk is clearly more acute in September, as central banks resume their policy meetings and parliaments return to work (see Figure 4). Even so, it is not obvious to me that major central banks will deliver the kind of surprises which cause major dislocations in financial markets. Lessons seem to have been learnt since the Fed’s 2013 so-called “taper tantrum” and I would expect central bankers to be particularly cautious in both their actions and words, forcing markets to focus on second or third derivatives.

The focus will be squarely on the European Central Bank (ECB) and US Federal Reserve meetings on 7th and 20th September, respectively, as central banks in the UK, Japan and Australia are seemingly content with doing very little at present.

European Central Bank sitting pretty for now

The ECB is ultimately in a pretty comfortable position, in my view, and can probably afford to do and say little next week. The Euro Nominal Effective Exchange Rate (NEER) has appreciated 5.5% since early May, which amounts to a tightening of monetary conditions and has led to speculation that the ECB will try to jawbone the Euro weaker. The minutes of the ECB’s 20th July policy meeting – which stated that “Concerns were expressed about a possible overshooting in the repricing by financial markets, notably the foreign exchange markets, in the future” were interpreted as evidence of a central bank keen to arrest the Euro’s appreciation.

But I am sticking to my view that the ECB is unlikely to actively talk down further modest Euro appreciation from current levels (see no UK rate hikes this year and room for further Euro upside 28 July 2017), highlighting five reasons. For starters, two key words stand out in the ECB statement: “possible” and “future”. That’s a far cry from saying that the Euro has already-overshot. It is also telling that ECB President Mario Draghi did not mention (directly or indirectly) Euro strength at the Jackson Hole meetings.

More fundamentally, financial conditions remain loose thanks to the fall in eurozone bond yields (see Figure 3) and decent performance of European equities. Fourth, eurozone macro indicators, including in Germany and France, are pointing in the right direction. Finally, the Euro NEER has been range-bound for the past few weeks (see Figure 5). While it has appreciated versus the Dollar and Sterling, it is down against the Chinese Renminbi (see Figure 6). The upshot in my view is that short of the ECB taking a sledgehammer to the Euro, I see the risk biased towards further EUR/USD and EUR/GBP upside in coming weeks.

French and German politics are unlikely to pose a significant risk to this constructive view of the Euro. President Emmanuel Macron presented on 31st August probably the most ambitious set of labour market reforms in decades which are due to come into effect via presidential decree in late-September. Resistance from the still powerful trade unions and opposition parties has so far been measured but history points to the risk of a more pronounced popular backlash in coming months. While this may further take the gloss off Macron’s presidency and dent his already faltering popularity, markets will have seen this all before so the bar has been set low for Macron.

German Chancellor Merkel is slowly gearing up towards federal elections in three weeks’ time. While the composition of the Bundestag, Germany’s house of parliament, may change to the detriment of Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU), she looks assured of a fourth consecutive term as I argued earlier this year (see Paradox of acute uncertainty and strong consensus views, 3 January 2017). Whether this is the optimal outcome for Germany is open to debate but markets are likely to welcome the political continuity.

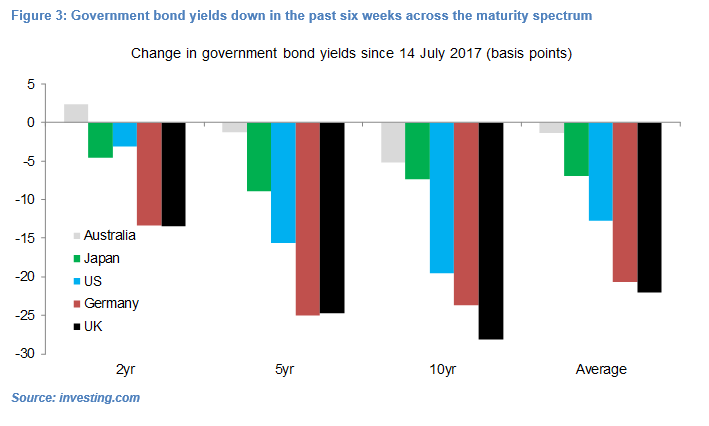

Federal Reserve is elephant in the room but I expect EM markets to avoid stampede

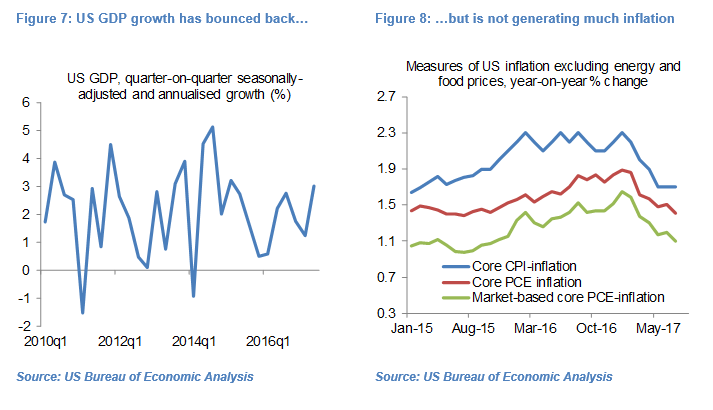

The Fed has arguably a trickier set of conditions to navigate. GDP growth is strong, the labour market is nearing full employment but real wage growth remains modest and core inflation is falling. The quarter-on-quarter seasonally-adjusted and annualised growth in the US was revised upwards to 3% for Q2 2017, the fastest growth rate since Q1 2015 (see Figure 7). But as Figure 8 shows, three key measures of core inflation continued to fall in July. Some FOMC members are seemingly keen to look through the lack of inflationary pressures and there is scope for US macro data to surprise on the upside in coming weeks.

The bottom line is that I am sticking to my long-held view that the Fed will only hike its policy rate twice in 2017 (see Politics suspected of interfering with economics and markets, 19 May 2017). However, very skinny market pricing of 8-9bp of hikes for the remainder of the year may not sit that well with the FOMC. I would therefore expect some kind of verbal intervention by Chairperson Yellen and other FOMC members to push up market pricing closer to around 15bp to help keep the odds of a December rate hike alive.

While the economic impact of Hurricane Harvey remains difficult to estimate, precedent suggests that major hurricanes have not stopped the Federal Reserve from hiking policy rates. Moreover, the Fed has flagged that it would likely announce at its 20th September policy meeting the beginning of a reduction in its balance sheet (effectively not buying back maturing bonds).

If misjudged and/or ill-timed these announcements could cause wobbles in wider financial markets, including emerging market (EM) equities, bonds and currencies which are already having to deal with the fall in crude oil prices. The consensus seems to be siding with a potentially sharp correction in global equities and EM asset prices. I am somewhat more sanguine about Fed announcements causing a wholesale disruption in EM markets. Macro data out of China are pretty buoyant, EM inflation is falling overall which gives central banks some scope to cut interest rates if necessary while FX reserves (particularly in Non-Japan Asia) provide central banks some room to support their currencies if corrections are disorderly and/or sustained.

UK – Glacial pace of change

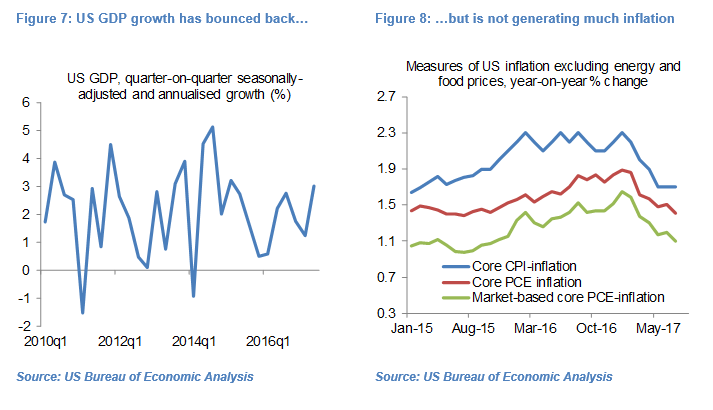

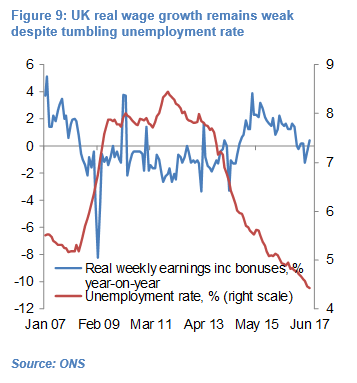

While May and June provided markets with plenty to ponder – including the ruling Conservatives’ botched general election and the slim possibility of the Bank of England (BoE) gearing towards a rate hike – the past couple of months have been low on excitement. I argued back in March that the BoE would not hike its policy rate this year and I have seen little evidence to change my view (see Bank of England and inflation – sense of déjà-vu?, 24 March 2017). GDP growth in coming quarters is unlikely to rise much from 0.55% in H1 2017 as growth in aggregate real weekly earnings remains turgid despite the record-low unemployment rate (see Figure 9).

The news flow on Brexit has somewhat cooled from the fever pitch earlier in the summer but two developments (or lack thereof) stand out. First and importantly, there is a now a seemingly solid consensus view among senior cabinet members, including Prime Minister Theresa May, that a transitional or implementation period would be required once the UK had left the EU in March 2019. Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hamond, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, Secretary of State for Exiting the EU David Davis, International Trade Secretary Liam Fox and Secretary of State for Environment Michael Gove have all in recent weeks given their backing for such an arrangement.

This is line with my expectation that a transitional agreement was the more likely outcome (See When two tribes go to war, 2 June 2017). Until recently the British government had repeatedly played down the need for such an agreement between the UK and EU. While the government’s position has yet to be formalised and finalised, markets have seemingly welcomed cabinet members’ meeting of minds. However, there is still much disagreement about a possible transitional agreement’s length and modalities, with estimates ranging from one to four years.

This uncertainty is being compounded by a lack of progress over the UK’s potential “divorce bill”. EU negotiators have repeatedly said that this stumbling block would delay the start of official negotiations over the terms and conditions of a new deal between the UK and EU.